On April 16, the Atlanta Writers Club and the Georgia Writers Museum will present its Townsend Prize for Fiction at Callanwolde Fine Arts Center. The award, given every two years to an outstanding Georgia author, is named for Jim Townsend, the legendary founding editor of Atlanta magazine. Ahead of the award ceremony, Georgia Writers Museum board member and writer Chip R. Bell reflects on Townsend’s storied legacy and his namesake award.

On April 16, the Atlanta Writers Club and the Georgia Writers Museum will present its Townsend Prize for Fiction at Callanwolde Fine Arts Center. The award, given every two years to an outstanding Georgia author, is named for Jim Townsend, the legendary founding editor of Atlanta magazine. Ahead of the award ceremony, Georgia Writers Museum board member and writer Chip R. Bell reflects on Townsend’s storied legacy and his namesake award.

Jim Townsend would disapprove of this article. While he would not fuss with the facts, the subject matter would give him pause. Jim was a person of the people who made you feel you were the most important human on the planet. And he kept his own character out of the mix. However, his legacy shines bright as the fruit of his works.

Townsend was the founder and longtime editor of Atlanta magazine, along with numerous other publications around the country. Time described him as “the father of city magazines”—over his career, he claimed to have “started, ran, edited, consulted upon, or served as publisher on 33 magazines.” His vision was the creation of a world-class magazine that modeled The New Yorker with smart writing, bold design, and compelling storytelling.

Townsend’s legacy lives on not only in the magazines he helped found–including this one–but in the Townsend Prize for Fiction, created in his memory in 1981 by a group of Atlanta writers. The Georgia Writers Museum, where I serve on the board, has worked with the Atlanta Writers Club since 2023 to administer the award, bestowed every two years on a Georgia author with the best literary fiction of late. Past winners have included Alice Walker, Mary Hood, Terry Kay, and Philip Lee Williams, to name a few.

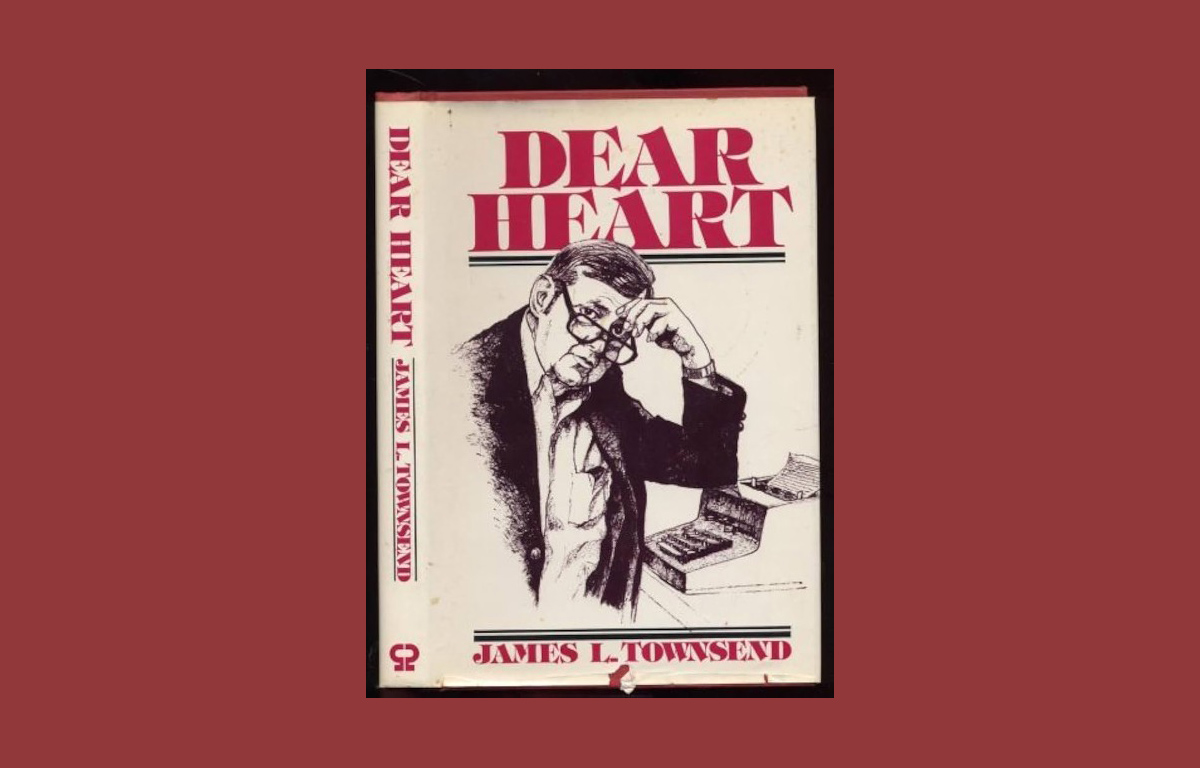

Photograph courtesy of Atlanta Writers Club/Georgia Writers Museum

This year’s award, presented on April 16, will select among ten finalists, whose books’ settings range from the banks of the River Niger in Southeast Nigeria to those of Georgia’s Ocmulgee River.

As my fellow writers and I prepare to celebrate Georgia’s greatest literary voices, I felt compelled to discover more about Jim Townsend, who himself cultivated many of those voices over the years. There must have been a good reason, I wagered, that this prestigious prize was named for him.

• • •

James Lavelle Townsend was born in 1933 in Lanett, Alabama, just over the GA-AL state line. That geographic fact is a metaphor; while his writing pen was in Georgia, his heart belonged to University of Alabama coach Bear Bryant. His writing career began at age twelve with a briefly-produced mimeographed gossip rag called the Lanett Gazette.

He attended the University of Alabama but left with plans to join the army, until an illness that robbed him of part of his lung blocked his enlistment. Instead, he hitchhiked all over the country, then set off to launch a career as a writer. It proved a quixotic journey: along the way, Townsend worked as a millhand, twice as a bank teller, taught writing to convicts in the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary, and was many times a car salesman. He never stopped being a salesman.

In early 1961 Opie Shelton, then the executive vice president of the Atlanta Chamber of Commerce, set out to build a magazine he would call Atlanta. Opie’s original goal was to feature articles written mainly by the chamber staff to showcase the city and encourage economic development. He hired Jim Townsend to make it happen–but Townsend’s vision, it turned out, was much grander and noisier.

The first issue, launched in May 1961, made up for what it lacked in editorial substance with stunning ads and breathtaking photography. But it telegraphed a potential for show-stopping journalism. Over the six years he helmed Atlanta, Townsend built the magazine into a journalistic juggernaut, and most importantly, a springboard for ambitious young writers who would go on to make their mark on the literary world.

“By nature, Townsend possessed the greatest attributes any editor can have,” Robert Coram wrote of Townsend in a 1996 retrospective for this magazine. “He could spot talent, nurture it, and give it a place to grow. He had a stable of stars and could pull stories out of them they didn’t know were there. If he ever put pencil to paper and edited any of those stars, that event has escaped notice.”

That stable of writers included authors who would become Georgia Writers Hall of Fame honorees, including Anne Rivers Siddons, Pat Conroy, Celestine Sibley, and Paul Hemphill. He had a knack for spotting creative talent, bringing on art director Bob Daniels, who would later become the art director of Esquire; Milton Glaser, who helped cofound New York magazine; and Vernon Merritt III, later a staff photographer for Life.

In his private life, Townsend was known as a defender of fairness and equity. “It did not matter if you were a CEO or a janitor, gay or straight, Black or white, in dad’s eyes, we are all the same—God’s children,” Towsend’s youngest daughter, Melissa Townsend Xydakis, told me. “I did not grow up knowing what racism was, and learning that later in life was a little shocking. I grew up with my dad’s friends being gay, Black, white, biracial, and some even being in trouble with the law and looking for a second chance.”

Those he hired saw him as a consummate mentor. “He not only saw the amazing in you, but he pushed you to see that same image and make it your standard,” recalled Terry Kay, who contributed to Atlanta and went on to become a best-selling author. He mentioned Townsend’s signature favorite line: “Write it down, dear heart, write it down.” It was more than a call for great productivity; it was a challenge to dream, soar, and be bold.

Another mentee, author Bernie Schein who was a member of Townsend’s close-knit drinking group, recalled in an interview how Townsend, after reading the draft of Bernie’s first book, told him, “Right now, Bernie, you are in the top 10 percent of the writers in the country. That’s how good you are.” Twenty-nine at the time, that encouragement compelled Schein to redouble his writing efforts; he went on to write three popular books.

After leaving Atlanta magazine, Townsend spent his final professional days working for Atlanta Weekly, an Atlanta Constitution Sunday edition magazine insert under the editorship of Lee Walburn. It was Townsend that Walburn turned to in his effort to unearth a story by Terry Kay that Kay had referenced in another Atlanta Weekly piece about his dad. When Townsend heard the “white dog story,” he again donned his mentor’s mantle and suggested Kay turn it into a book. To Dance with the White Dog became Kay’s biggest worldwide bestseller and an Emmy Award-winning movie.

After winning a hard-fought battle with alcoholism, Jim lost his battle with cancer (a malady he provocatively referred to as “Louie”). He died on Sunday evening, April 6, 1981. His friends founded The Townsend Prize in his memory that same year.

Townsend’s namesake award affirms those with the gift of literary magic; those searchers who hear the melody of nature, feel the mystery of character, and see the beauty of story. It is the perfect legacy for Jim Townsend: a dreamer who saw the best in writers, and in the art of the storytelling itself. For he was, as he once put it, just “an old con who has heard just about every story a man ever believed and had believed every one of them himself.”

The 2025 Townsend Prize for Fiction will be awarded on April 16, 2025, at the Callanwolde Fine Arts Center in Atlanta. Tickets are available by contacting the Atlanta Writers Club.

Chip R. Bell is an international best-selling author and serves on the board of Georgia Writers Museum.

Advertisement