Photograph by David Raccuglia

Atlanta-based artist and performer Lonnie Holley never plays the same song twice. Not because of some avant-garde decision but because at seven years old, he says, he was struck by a car and spent the next three and a half months unconscious. “They considered my brain dead,” says Holley. “Ever since then, it’s been a struggle to keep reviving my own brain to a point it can be productive.”

That struggle has not impeded Holley’s creativity. His process, what he calls “thought-smithing,” involves “plundering” each thought for its creative material and bringing that to other collaborators. The thought-smithing and the output happen concurrently, with Holley improvising music and lyrics that evolve from event to event. “So instead of me having to worry myself with a redo [of a song], I was always naturalizing,” he says.

Art © Lonnie Holley / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; courtesy of the artist and Blum Los Angeles, Tokyo, New York. Photograph courtesy of Jagjaguwar Steve Pitkin / Pitkin Studio

Through thought-smithing, this septuagenarian songster has produced five studio albums since 2012. His latest, released in March, is Tonky—his childhood nickname from when Holley lived in a honky-tonk.

The album’s opening track is also its longest: a nine-minute, atmospheric piece called “Seeds,” about Holley’s traumatic time as a minor at the infamous Alabama Industrial School for Negro Children. The song starts with a plaintive moaning violin and the steady march of handpan metal drums, building into an emotionally packed chorus of strings, chants, synthesizers, and Holley’s inimitable brassy voice. He groans sinisterly:

They take the sheep shears and they’ll cut an X in your hair

So they’ll know you are a product of the Alabama Industrial School

Oh I wish that I could rob my memory

I’d be like Midas and turn my thoughts to gold

And one day end up just being alright

Where I wouldn’t do nothing to lose my soul.

Holley’s lyrics pack such a lasting, Dylan-esque punch, it’s hard to believe they’re largely improvised. But Tonky is not all doom and gloom. This album veers from boogying and rocking—with tracks such as “What’s Going On” (featuring Modest Mouse creator Isaac Brock)—to gospel-like inspiration in a completely reimagined version of Sam Cooke’s “A Change Is Gonna Come.”

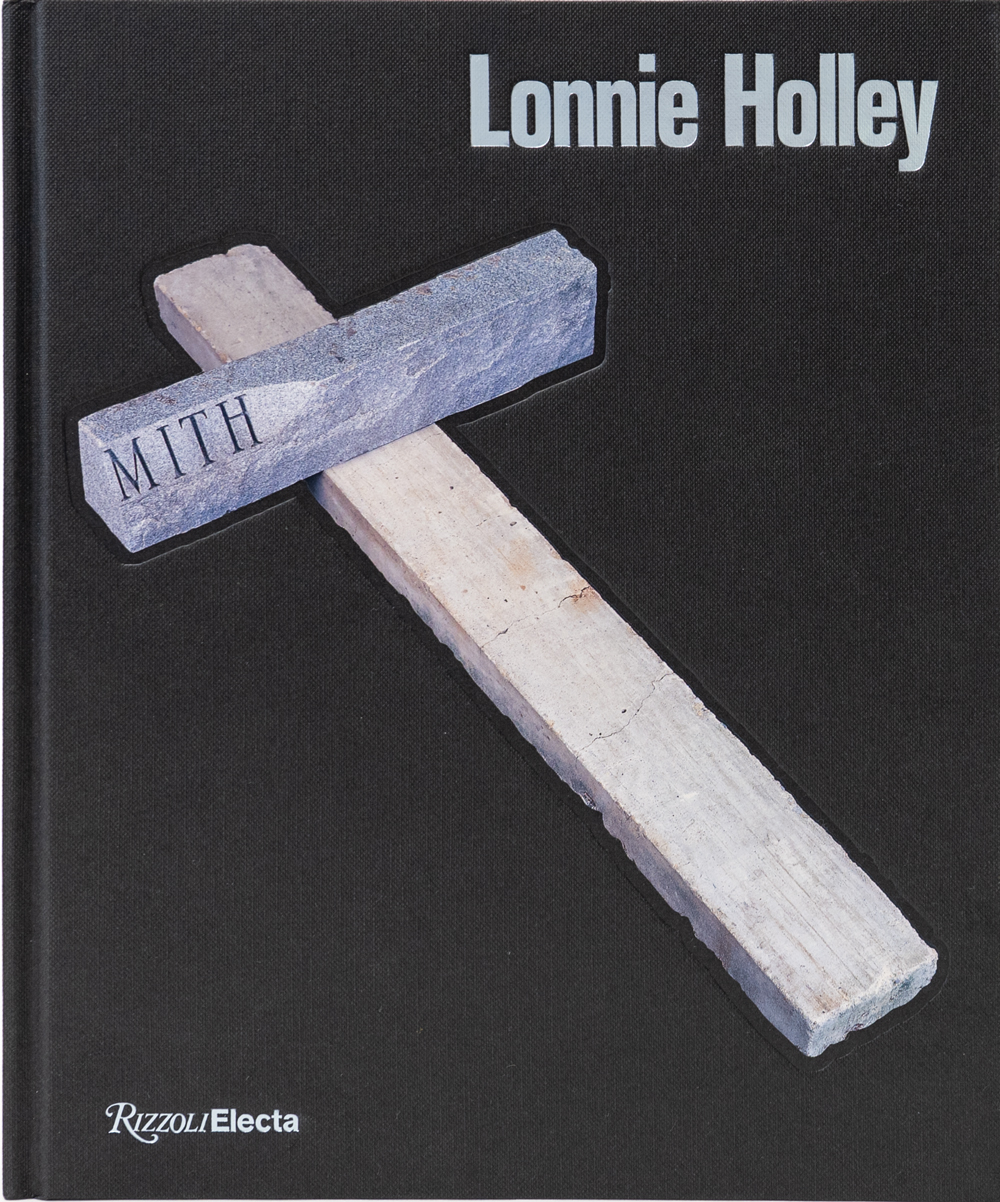

Art © Lonnie Holley / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; courtesy of the artist and Blum Los Angeles, Tokyo, New York. Photograph courtesy of Rizzoli New York

But the album was only part of Holley’s busy year: Tonky’s release followed on the heels of the first coffee-table book about the artist, called Lonnie Holley. This 250-page monograph, written by Harmony Holiday and John Beardsley, catalogs the artist’s life and work, from his early years in Birmingham as the self-styled “Sand Man,” where he created his first sculptures from a sandstone-like industrial by-product, to his rise to fame exhibiting works around the globe.

Holley’s story reads like a Southern Gothic novel mixed with a Dickensian rags-to-riches tale. Born in 1950, Holley was the seventh of his mother’s 27 children, out of 32 pregnancies, and was later sold for a pint of whiskey.

Art © Lonnie Holley / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; courtesy of the artist and Blum Los Angeles, Tokyo, New York.

His creative career began in 1979, when Holley carved two sandstone tombstones for a niece and a nephew killed in a fire, and felt a “divine intervention” to keep creating art. Two years later, Holley pulled up to the Birmingham Museum of Art with several of his sandstone sculptures. Then-director Richard Murray was blown away. He displayed the pieces and later introduced Holley to the organizers of the 1981 Smithsonian exhibition More Than Land and Sky: Art from Appalachia, which would feature Holley’s art at a national level.

“I’ll never forget it,” says Holley about Murray. “He [became] one of my best friends. It almost brings me to tears to think about all the people who’ve been in my life to help keep me motivated and spiritually charged to do whatever I’ve done.”

At 75, Holley remains prolific. And 2025—with the dual album-book release, a talk at The Carter Center this month, plus a European tour—might just be the year of Lonnie Holley.

This article appears in our April 2025 issue.

Advertisement