Photograph by Kim Kenney

Not long after he had taken over as executive director at Atlanta Ballet in 2021, Tom West and his board of directors had to make one of the toughest decisions in the company’s history. Last August, they did something rather startling: They sold their headquarters—the Michael C. Carlos Dance Centre—for $8.3 million to Faropoint, a New Jersey real-estate investment firm.

It wasn’t an easy decision. Coming out of the Covid-19 pandemic, Atlanta Ballet— founded in 1929 and the longest continuously operating ballet company in the United States—found itself $2 million in debt.

The cascade began when the ballet was unable to negotiate a deal with the Fox Theatre to continue staging choreographer Yuri Possokhov’s acclaimed new take on The Nutcracker. In 2020, the production was set to make its debut at the Cobb Energy Performing Arts Centre, but it was canceled due to the pandemic, along with two productions scheduled for that spring. The ballet ended the year with a shortfall of $3 million.

Photograph by Shoccara Marcus

“In the economics of a ballet company, The Nutcracker is really the only thing that makes money, and it funds the other artistic investments of the season,” says West.

When restrictions were lifted, audience habits had changed, and it was a challenge to draw them back to live performances. West says moving The Nutcracker out of the Fox hurt. Many patrons didn’t want to venture outside of Midtown, and the company lost more than a million dollars two years in a row.

Making matters worse, in February 2023 the ballet company’s bank pulled its line of credit at a time when it was needed most, expressing doubt in the company’s ability to rebuild. For the next 18 months, Atlanta Ballet tried to keep its head above water. Leadership explored several options, including talking to major institutional and individual funders, and even considered borrowing against the equity in the building.

Photograph by Kim Kenney

Photograph by Kim Kenney

The sale leaseback on the headquarters didn’t become a strategy until later that summer. “A number of donors, particularly in the philanthropic community, were not ready to step forward for the ballet,” West says. “To me, that indicated that we needed a significant rebuilding of confidence in the operations and in the management of the company.”

During internal conversations, a new idea emerged. Mark Bell, a member of the committee, reminded the group that they were in the business of educating young people and presenting great art. “You are not in the real-estate business—is owning your property really essential, or should you look at it differently?” Bell asked ballet leadership.

Convinced a sale leaseback was the path, the team moved forward. The process of finding a buyer and working out a deal took roughly a year.

Atlanta Ballet is now renting its west Midtown headquarters on a 10-year lease, with two five-year extensions at fixed rates.

West says the lease gives the company flexibility for the future. “We have the right of first refusal if they decide they want to sell it to another investor,” West says of Faropoint. “As we get through our 100th anniversary, we have the option of whether we want to be here until perpetuity and repurchase, or if we want to take the time left on the lease and purchase and develop a new facility.”

The sale gave the ballet about $8 million of breathing room. “It got me and my senior leadership team out of the bunker,” says West. “It allowed us to shore up our operating reserves and give us operating cash for the next few years while we rebuild the fundraising and marketing capacity.”

Photograph by Kim Kenney

West now feels a lot more secure about the ballet’s future: “When you are focused on [whether you’re] going to be able to make payroll in a month, you don’t have the bandwidth to make longer-term strategic decisions.”

Nello McDaniel, founder of the New York–based arts consulting group Arts Action Research, says the move is not unprecedented. The Connecticut-based Long Wharf Theatre sold its headquarters in 2022. “I’m not surprised what anyone has to do coming out of this pandemic, trying to find a way to regain a sense of balance and serve visions and missions,” he says.

Atlanta Ballet is in the process of launching an internal committee focused on funding new artistic programs. The goal is to bring “world-class” productions here and to commission new works that the ballet will own.

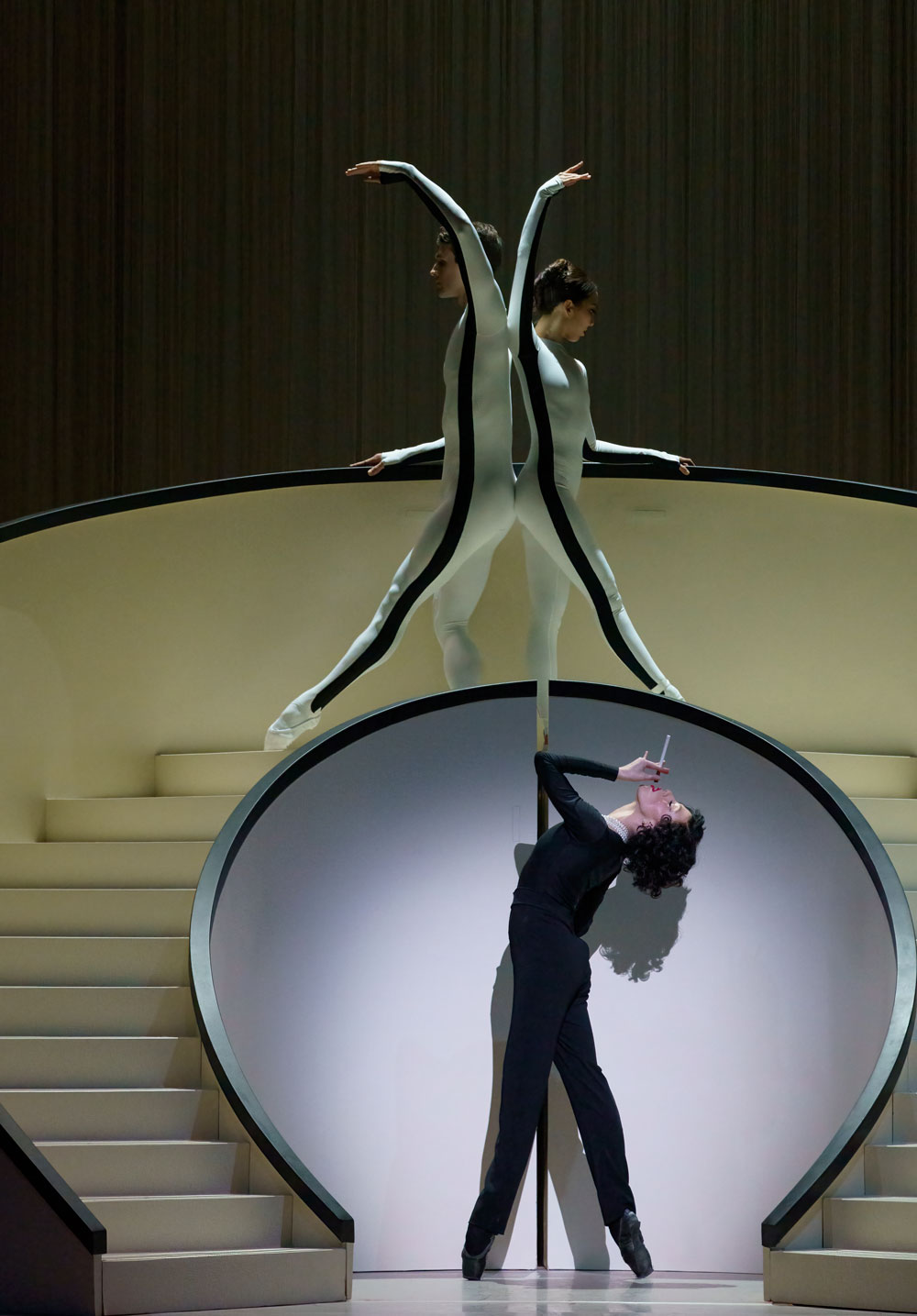

Photograph by Shoccara Marcus

Photograph by Kim Kenney

One example is last year’s Coco Chanel: The Life of a Fashion Icon—a cocommission between Hong Kong Ballet, Queensland Ballet in Brisbane, and Atlanta Ballet—had its North American premiere in Atlanta last year. Choreographed by Annabelle Lopez Ochoa, the show was a success, artistically and financially.

West says the production had $610,000 in ticket sales. “We wanted something coming out of the pandemic that would spark the interest of the community beyond ballet lovers, that would break through the noise, is reflective of our standards—and was affordable,” he says. “Subscriptions to the following year grew. It broke the ballet out as more than a niche art form. It was very accessible to the broad public.”

Among the 2025–26 offerings will be Frida, a tribute to Frida Kahlo choreographed by Ochoa, and a new version of Giselle.

Throughout his career, West has grown accustomed to staring down crises. He was working at the Kennedy Center during 9/11, the Orange County Performing Arts Centre (now the Segerstrom Centre for the Arts) during the recession of 2008, and the American Film Institute during the pandemic.

He learned to face a problem and find a solution. “You pause, define it, and figure out what your nonnegotiables are,” West says. “For us, it is the people—the artists, the creative collaborators, the staff. They are our biggest asset. We are investing in the right way for the future so we can take care of them.”

This article appears in our August 2025 issue.

Advertisement