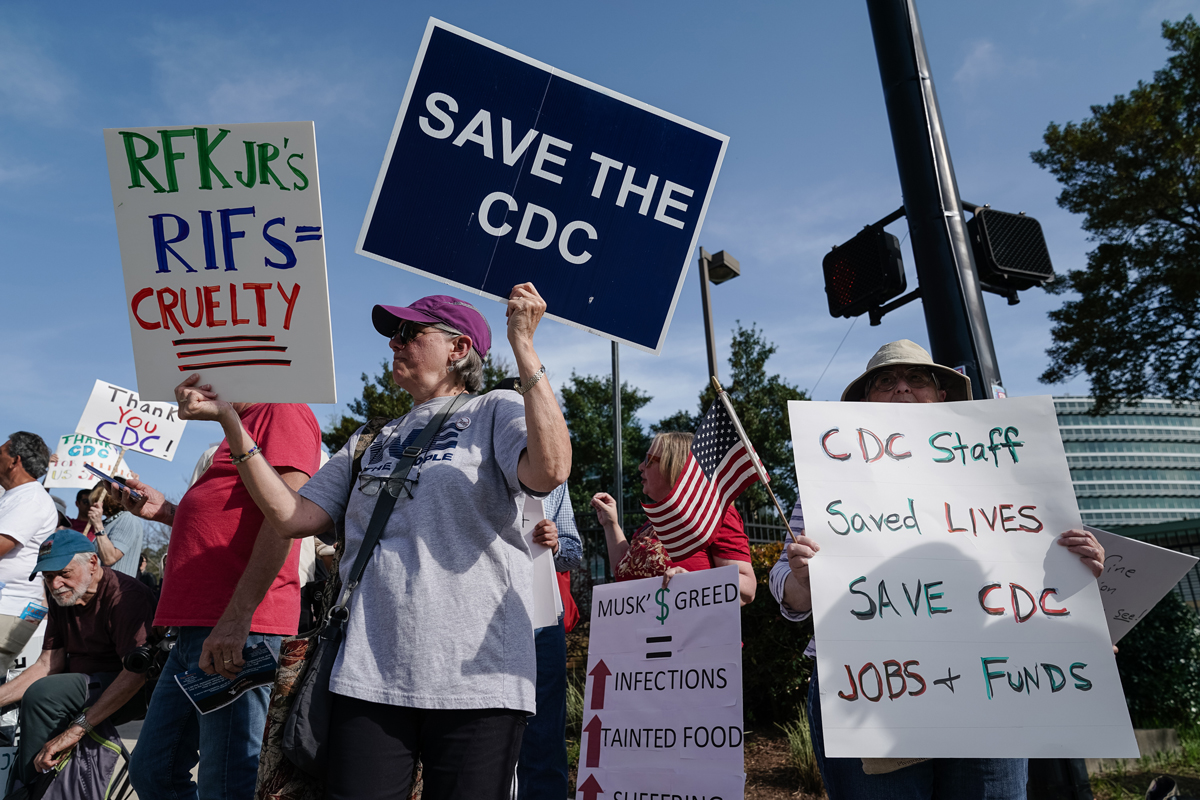

Photograph by Elijah Nouvelage/Getty Images

Editor’s Note: The names in this story have been changed to protect anonymity of former federal workers.

The sun hadn’t yet come up when Charles’s phone started ringing on the morning of April 1. A colleague at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention told him employees were receiving reduction in force (RIF) notices as they arrived to work at the Clifton Road campus. Charles found one waiting in his inbox, too.

That morning, 2,400 CDC employees were given RIF notices with no explanation of which positions were being eliminated or why. “It was surreal—nobody knew who was in and who was being let go,” Charles told me during our first conversation, just a few weeks after the mass cuts.

Charles, who worked at CDC for 15 years as a data scientist focusing on preventable injuries, spent hours on the phone that day trying to find out who else had been affected. He soon pieced together that his entire team had been let go. “I’m a big Marvel fan, and I liken it to when Thanos snapped his fingers [in Avengers: Infinity War] and random people started disappearing,” he says. “That’s what it felt like.”

Alice, another CDC worker, woke up that morning to a text from her manager telling her to check her email, because both her manager and her manager’s boss had received RIF notices. Alice had, too. She drove straight to the office to clean out her desk before losing building access. “I was doing fine, and then about three-quarters of the way through the drive [to work], I just started sobbing,” she says.

For Alice, the CDC was a dream job: she moved to Atlanta for the position, and excitedly bought a condo a few miles from CDC’s campus. “I was convinced I was going to retire from the CDC,” she says, adding that many of her colleagues, some of whom had worked there for decades, were planning the same. “People are devastated . . . it has been a life’s passion for us.” In her role, Alice collaborated with external research partners to study and address issues like bicycle helmet safety, teen dating violence prevention initiatives, naloxone efficacy for opioid overdose, and traumatic brain injury guidelines. “These are real-world things we can think about that have made people safer,” she says. “And without funding to continue researching these things, people will die or be severely injured.”

If April 1 was chaotic, the months following it were even murkier. “There were so many questions, but no one was able to answer them,” Charles says; the CDC’s Human Resources department was also gutted by the cuts. Charles, Alice, and their RIFed colleagues were told they’d be placed on administrative leave until June 1, when their termination would be made official. Instead, they lingered in limbo through the summer as their fates played out in the judiciary system—unable to do their jobs yet still being paid to do them (despite the cuts being made in the name of government efficiency), and with no clear answers about severance pay or health insurance. “There was absolutely zero communication,” Charles says. “We were left in the dust.”

In the absence of HR support, former CDC employees like Charles and Alice resorted to group texts, Signal chats, subreddits, and crowdsourced Google docs to piece together information.

Many of the RIFed workers spent their administrative leave searching for employment, entering a bleak job market in a field beset with funding cuts, struggling to figure out how to translate their professional skills to the private sector. (“We don’t often build skillsets that can drive profits for private companies,” Charles explains.) In June, several hundred RIFed CDC workers were reinstated. Many others still on leave chose to hold off on job-hunting, hoping the courts would allow their RIFs to be rescinded, too—and if not, hoping for termination benefits, something they would be ineligible for if they voluntarily resigned for another job before being officially let go. Meanwhile, the legal status of their RIFs went back and forth through preliminary injunctions, appeals, and stays across multiple concurrent legal cases.

Then in August—just weeks after an active shooter fired 500 bullets on the CDC campus and killed a DeKalb County police officer—a federal judge narrowed an injunction that had temporarily protected all CDC workers. Only six centers remained shielded, leaving the door open for the administration to fire CDC employees in other departments.

A few days later, Charles was invited to a last-minute Zoom call in which he was told that his position was being reinstated—and he had until the end of the day to decide whether or not to return. It had been nearly six months since the April cuts, and Charles had finally secured a new job in the private sector just a few weeks prior. “I was just in shock,” he recalls. He decided not to return to the CDC.

“It was much more emotional for me to quit than to have been fired originally,” Charles says. “It’s one thing to be fired outside of your control. It’s another to decide to walk away from your career.” The reinstatement news came during the same week that the White House abruptly fired the CDC’s director after her clash with Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. over vaccine policy, prompting several other CDC leaders to resign in protest. What Charles saw as a vacuum of trustworthy, principled leadership was a grave concern. “Now, no one’s up there that is advocating for us or advocating for our science,” he says. “That’s a really bad situation.”

Charles was one of a relatively small group who were offered their jobs back in August; other workers in the six agencies protected by the injunction are still on administrative leave until the legal challenges are resolved. The rest—about 600 people—were finally terminated in August, about a week after the revised injunction. Alice, who worked in the Injury Center, was among them, bringing several painful and confusing months to a close. In late August, her termination letter arrived, just shy of her two-year anniversary. “Honestly, I knew it was coming,” she says, “but I was a lot more sad that week than I thought I was going to be.”

Following her RIF in April, Alice had already begun job-hunting, but the market was grim. Of her CDC network, she only knows two people who have found jobs in the field. Others have taken minimum-wage jobs to get by or moved back home to save money. “It’s a really bad market, and people are not having good luck,” she says.

Public health is where Alice finds a sense of purpose, and, as demoralizing as the last few months have been, she’s choosing to believe that the CDC will eventually be able to rebuild. After her termination was finalized, she decided to work with an attorney to file an appeal with the Merit Systems Protection Board, which handles wrongful termination complaints for federal workers, in hopes that she might be reinstated. “I don’t know what the chances are of that actually happening, but I figured I might as well try,” she says. “I really hope that we’re going to take the best things about public health from before, and improve on the weaknesses, and come back better and stronger.”

When we spoke in April, Charles described a sense of “overarching sadness”—sadness for his colleagues, but also for the country. Speaking with him again in August, he said that while he felt personally fortunate to have found employment, the past six months left him and his colleagues feeling “stripped of our dignity and our passion.” From the leadership shakeups to the gutting of the CDC’s vaccine advisory panel to a misinformation-fueled shooter attacking the agency’s headquarters just months after its firearm experts were RIFed, Charles felt “like a ghost in the room” watching the hollowing-out of public health from the sidelines.

“When you dismantle public health institutions, you don’t see an immediate effect,” Charles told me back in April. “There is no instant sort of consequence of removing public health institutions. But public health institutions have always been focused on the future. The impact may not be felt by the public immediately, but it will definitely affect the public, in ways that are now potentially unmeasurable.”

Advertisement