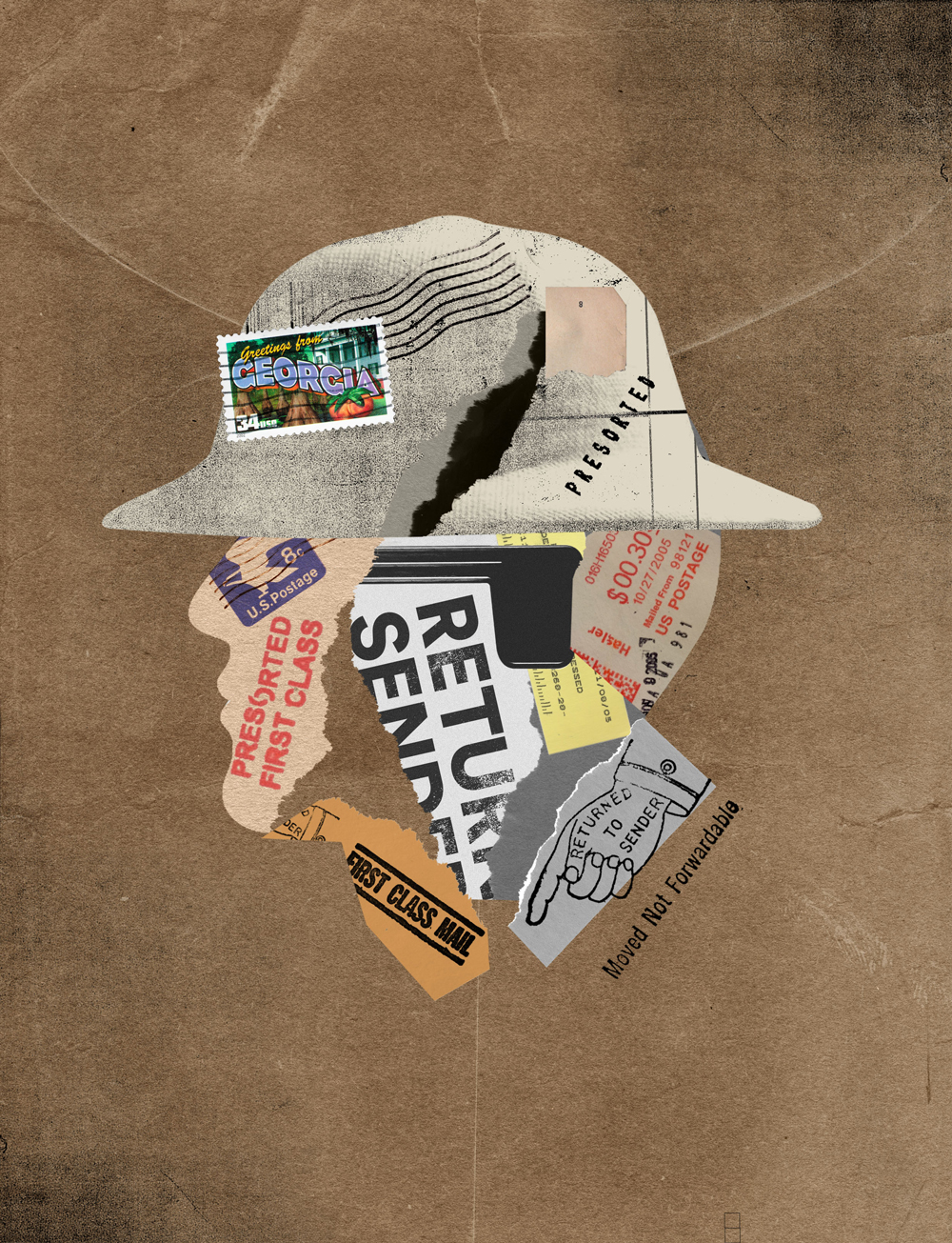

Illustration by Mark Harris

Asked to recall a low point for Georgia’s monthslong, mail-service debacle of 2024, the state’s U.S. Senator Jon Ossoff thought back to a day in June on the Fulton County Courthouse steps. There, the first-term Democratic senator stood with Ché Alexander, Fulton County clerk of the Superior & Magistrate Courts, next to large bins brimming with more than 1,000 pieces of mail, all marked “return to sender.” That mountain of misguided mail had been returned to the court in a single three-day stretch. Some of it had been postmarked years earlier. None of it was birthday cards or frilly wedding announcements.

“We’re talking about notices to appear in court—notices of eviction,” said Ossoff. “It’s probable that people were locked up or lost their homes because of postal failures.”

The situation in Fulton County was emblematic of a greater U.S. Postal Service breakdown that began in 2023, crippling on-time mail-delivery rates across Georgia and eroding public trust in the basic capabilities of the federal mail agency. The problems have drawn bipartisan scrutiny and inspired Ossoff to pursue reform.

In late winter 2023, the senator’s office began logging complaints from constituents across Georgia, opening thousands of cases on their behalf. Along with crucial documents such as court orders, prescription medications weren’t being delivered to many Georgians. Small businesses weren’t receiving supplies needed for their operations—or their mailed products weren’t reaching the market. Requested absentee ballots were never received. The whole snafu (stronger, more profane words are applicable, Ossoff says) proved that while the postal service may play a diminished role in American society in the age of FedEx, UPS, and Amazon, the old-school mail system remains not just an economic necessity but a vital lifeline.

So what happened? And what’s being done to fix it?

Photograph by Getty Images

The postal service has been grappling with spiraling revenues and a nationwide slowdown in mail delivery for years. According to the Associated Press, the service hemorrhaged $87 billion in losses between 2007 and 2020, and the volume of first-class, single-piece mail has dipped by 80 percent since the late 1990s as the amount of packaged shipments has grown. In late 2023, postal officials reported another $6.5 billion loss—despite price hikes on stamps—as first-class mail, the most popular means of paying bills and sending letters, sank to its lowest volume since 1968.

The internet is partly to blame—email and social media have largely replaced “snail mail”—as is the postal service’s raison d’etre: Although the U.S. Postal Service receives no federal funding (it’s the only federal agency required to pay for itself), it must deliver to every single home in the United States, regardless of how perilous, or simply unprofitable, the route. (Amazon and FedEx pay the postal service to deliver “last mile” packages to addresses to which the companies won’t send their drivers.) In 2006, Congress passed a controversial law requiring the service to prepay its pensions, sinking the agency even further financially, though a reform act passed in 2022 partly did away with that law, including the pensions provision.

Photograph by Getty Images

In 2021, U.S. Postmaster General Louis DeJoy, appointed the year prior by a governing board selected by then-President Donald Trump, announced a controversial 10-year reorganization plan for the agency. Under his plan, DeJoy promised, the USPS would break even in 2023, wipe out $160 billion in forecasted losses over the next decade, and avoid a government bailout.

So far, DeJoy’s restructuring goals haven’t played out as planned. In Georgia, things went particularly haywire beginning in February 2024, after the postal service opened a facility in Palmetto, half an hour south of Atlanta, as part of a plan to consolidate smaller mail operations into larger regional facilities. These modernized facilities were supposed to be more efficient and better equipped to handle surges in packages. Within weeks of the facility’s debut, however, all hell broke loose—logistically speaking.

Palmetto’s mail-processing bottleneck was so severe, employees who’d relocated from across Georgia complained to local media that they were running out of space to store letters and packages in the overwhelmed 1-million-square-foot distribution center. Long lines of mail trucks snaked around the facility onto nearby highways.

Customer complaints poured in as notices were taped up in post offices around metro Atlanta warning of delays. A postal service performance report ranked Georgia dead last nationwide in terms of first-class mail transit time: After the Palmetto facility opened, on-time deliveries dropped from 90 percent to a shocking 36 percent, before leveling out to 63.7 percent in the second quarter of 2024, well below the national average of 87 percent.

Ossoff visited Palmetto in May and was outraged. “I asked a table of senior USPS managers [at the distribution center] who was in charge of implementing the changes they were trying to make in Georgia, and there was a very long silence,” said Ossoff, “because no one was in charge.”

The following month, the facility brought in more management; at a press conference in front of the Palmetto distribution center, a trio of Republican U.S. representatives assured constituents that corrections were coming within eight weeks. Indeed, by summer 2024, on-time delivery rates had climbed back above 80 percent, and Ossoff says the “intensity and volume” of constituent complaints has ebbed.

Photograph by Getty Images

Problems persist, however. According to Henry County Tax Commissioner Michael Harris, an “enormous amount” of tax bills mailed in late August came back to his office, even though the addresses on the envelopes were correct. As Harris says he’s explained to postal officials on several occasions, Henry County had paid about $52,000 for first-class postage, and with so much returned mail, the risk of residents being hit with late-payment penalties is great. The issue could result in a reduced collection rate and diminished cash flow—which would, in turn, negatively affect county and city government coffers and ultimately the school system.

Ossoff believes the postal service’s long-standing structural challenges were compounded by DeJoy’s counterproductive attempt at mail-flow reform. DeJoy, a business executive and major Republican donor who had no prior experience with the service before his appointment, had no qualifications to run such a complex and crucial operation, Ossoff argues—a point he made clear during a heated Senate committee hearing face-to-face with DeJoy in April 2024.

At the hearing, Ossoff told DeJoy, “You don’t have months to fix 36 percent of the mail being delivered on time . . . You are failing abysmally to fulfill your core mission in my state.”

In the wake of Georgia’s mail collapse, Ossoff has pushed for more significant changes. In September, he introduced the Postmaster General Reform Act, which would give Congress more control over selecting postmasters general by requiring the Senate to vet candidates prior to any confirmation. It would also limit postmasters to two five-year terms: Currently, there is no cap, and the only authority that can fire or remove the postmaster general is the USPS Board of Governors (of which DeJoy is a member).

“Effective postal service is not a luxury. It’s a necessity—and a reasonable expectation of the American people,” said Ossoff. “It’s an embarrassment that in the same country where the Normandy Invasion was planned and the Apollo program was executed, our postal service can’t deliver the damn mail on time.”

This article appears in our January 2025 issue.

Advertisement