Photograph by Allan Detrich

MANY WHO DISAPPEARED into Faye Yager’s underground first passed through Atlanta—and still speak in awe of “the Mansion.”

“I always think about that house,” says Mandie Ervin, who was six when she lived here with her mother as fugitives for about three months in late 1991. “It was so big.”

An opulent, 19-room Tudor home on fashionable Curlew Court in Sandy Springs, it stands five stories and, in those days, often had a Rolls-Royce parked in front. That was at the height of Faye’s fame as a crusader for sexually abused children and just before her very devoted husband depleted his entire wealth, spending whatever it took to defend her against criminal charges.

Ultimately, several years later, even the house was sold.

“Faye knew she was doing the right thing,” says Dr. Howard Yager. “She was very, very strong.” He quickly adds, “I was stressed to the max.”

Faye, who died on August 3 at age 75, was a housewife and mother of five, an interior designer with a penchant for collecting fine antiques, and an expert cook who could improve pretty much any recipe with a pinch of this or that. And for over a decade, she also built and operated a sophisticated, clandestine network to help hundreds and perhaps thousands of abused women and children disappear and start new lives.

“Otherwise,” Howard says, with no humor intended, “we had a perfect marriage.”

❦ ❦ ❦

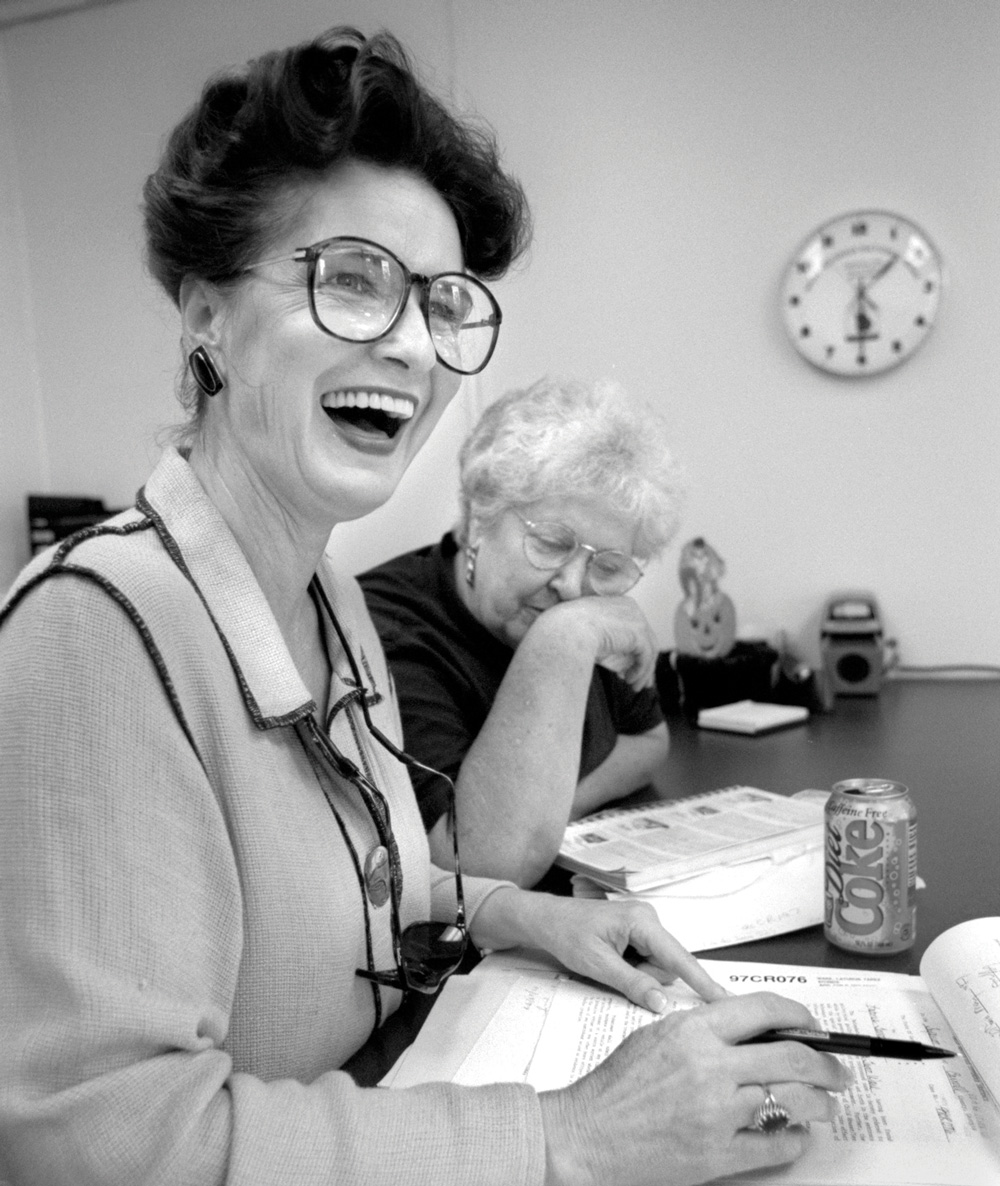

“THE ONLY REASON I’M TALKING TO YOU is Howard Yager says I can trust you,” she declared bluntly, the first time I visited her at the Mansion, in 1998.

Wearing the apron she donned whenever she entered her house, Faye Yager spoke tersely, with a clipped, no-nonsense, distinctive Southern twang I’d heard before—on numerous television appearances and in a courtroom—sounding more like a reproachful librarian than the nation’s best-known vigilante.

I’d covered her dramatic criminal trial in 1992 but didn’t yet know her.

A phone in the kitchen rang almost constantly. Some were calls from mothers asking her for help, but most were pranks and harassment, including anonymous threats to kill her husband or rape her children. Private investigators and bounty hunters had contacted her friends with reward offers for information. Dead animals were left on the doorstep.

“It’s horrifying,” Faye said. “I’d have to be stupid to sit here and tell you this is not scary.”

Her husband happened to be my doctor. Though her name had never come up in our conversations, during an office visit one day, Dr. Yager asked if I knew who she was and whether I’d like to have her last interview. Faye had not yet announced she was preparing to give up the organization known as “Children of the Underground” for a simpler life operating a bed-and-breakfast in North Carolina.

Fathers of missing children had grown in number and organized. The one who worried her was a millionaire named Bipin Shah, a developer of the ATM. Shah was determined to locate his ex-wife—who accused him of spousal abuse—and two daughters, and with a $2 million reward, he ultimately did, in Switzerland. Even though Shah was never accused of abusing his children, Yager had accepted them into the underground, violating her own protocol. She knew Shah was about to appear on the cover of Time magazine to publicize his search and that Connie Chung was working on what Faye described as a “hit piece” for ABC’s 20/20.

“If they’ve abused a woman and they can’t get to her anymore, then I become the batting cage they go after,” she said.

A self-taught expert in the art of creating false identities and obtaining birth certificates, passports, and other government documents needed to support new lives, she was lauded by many as a fearless protector who stepped in when the justice system failed. She was also decried by others as a dangerous avenger taking the law into her own hands.

In the ’80s and ’90s, Faye Yager gained widespread notoriety as a fierce and occasionally reckless advocate for child victims of sexual abuse at a time when the subject was barely acknowledged or discussed. Sharp-tongued, outspoken, and reliably sensational, she became a staple on daytime talk shows of the era.

Almost always, her youngest son was backstage or in the studio audience, taking in everything. As a boy, Josh Yager was never far from her side. “She took me with her everywhere she went,” he says.

Photograph by Allan Detrich

Most days, they could be found at the Dunkin Donuts on Roswell Road—the de facto headquarters of Children of the Underground—where employees allowed Josh behind the counter and kept him entertained while Faye sipped coffee with a “Sally,” the code name for women who came to her for help.

“The people who worked at Dunkin Donuts loved her,” he says. “They let her take calls there and were very protective.”

Josh was in the car when Faye drove to a post office box she checked daily, to the pay phone she trusted, to meetings in parking lots where documents and envelopes were passed back and forth, and to a Holiday Inn she frequently used as a hideout for mothers on the run with their children. After that, they might head up the street to peruse new items at an auction house or drive to a farmers market to pick out something to cook for dinner.

Howard, after a full day of treating patients, would return home to one of the best meals in Atlanta, blissfully unaware of what Faye had been up to all day and asking few questions. “The less I knew about it,” he says, “the less I could be examined about it.”

But he adds, “A lot of people were going in and out of my house.”

❦ ❦ ❦

WHILE PREPARING TO ENTER THE UNDERGROUND with her mother in 1991, Mandie Ervin took part in Halloween for the first time at the Mansion. The holiday had been considered off limits because of her family’s strict religious beliefs, but Faye Yager dressed her in a costume, painted her face, and sent her door-to-door on the cul-de-sac.

“It was a really pretty neighborhood,” Mandie remembers. “I recall going trick-or-treating with a girl who was much older than me, and I think that was Faye’s daughter.”

If not exactly thrilled, the Yager children were accustomed to strangers in and out of their home and often kept to themselves or were away doing their own things. Mandie has a distinct memory of one of Faye’s teenage sons bursting into the house one day and, without speaking to anybody, rushing upstairs to his room, slamming the door, and “blasting” the new R.E.M. song, Losing My Religion—a teen anthem about acute frustration and being at the end of one’s rope.

“You can’t imagine the constant chaos, just the personal toll that the whole family took in this pursuit of hers,” says Dr. Joshua Yager, now 40 and married with two young daughters. Proverbially following in the footsteps of his father, he’s a successful physician with his own family practice in Chamblee.

He has never doubted the righteousness of the cause to which his mother devoted so much of her life. But that didn’t make things any easier when he and his siblings were growing up.

“We believed in what she was doing, so it was a very willing sacrifice,” the younger Dr. Yager explains, speaking slowly and choosing each word carefully. “But it’s not an easy

sacrifice. It was an extremely, extremely tough sacrifice.”

Says his father, “Every day was a new challenge.”

❦ ❦ ❦

“I DID WHATEVER FAYE ASKED me to,” April Curtis says. “I would do anything for that woman.”

In many ways, April and Faye built the underground together. In an emotional interview, she revealed more than she ever has about the extent of their relationship, which both women had reason to downplay until now. Even April’s father and stepmother became involved, providing safe haven in Oregon for women and children on the run whenever Faye called, which was often.

“I don’t trust many people at all,” April says. “My whole life has been affected by my time in the underground. My entire life. Working under the table during those years,

I just don’t ever feel like I can ever trust again, and especially men, and especially the justice system. It’s still very hard for me because there’s still a lot of anger I have, and I try to deal with that every day.”

Children of the Underground did not yet exist by that name in early 1988 when April fled California with her daughter, Amanda, following sexual abuse allegations against the child’s father. “She was three!” April says, weeping.

She had been a fugitive for two months when she found Faye. “When I first heard about the underground, I thought it was all set up and everything, and then later found out Faye was just one step ahead of me,” April recalls. “She didn’t have a lot of ‘safe homes’ ready.”

April and Amanda would hide out briefly at the home of Faye’s mother in West Virginia, then in Atlanta at the Mansion. But, first, they embarked on a daring publicity tour.

Faye had been talking to an investigative reporter at U.S. News & World Report, but the story moved from obscurity to prominence when April agreed to let the magazine publish a photograph of her with Amanda on the cover.

A month later, actively sought for kidnapping, April made another risky appearance with Amanda, being interviewed as guests on an episode of The Geraldo Rivera Show titled “Parents on the Run.”

“Is your daddy a good man, or do you think he’s a bad man?” Rivera asked four-year-old Amanda.

“He’s a bad man,” Amanda responded.

Rivera turned to ask the opinion of an expert seated next to them, psychologist Larry Spiegel, who had been invited on the show as an advocate for fathers unjustly charged with child abuse. “She should not be believed,” Dr. Spiegel replied.

Despite having been acquitted in court on charges involving his own daughter, Dr. Spiegel’s wife and children had disappeared—with Faye’s assistance. He was unaware Yager was in the audience, wearing sunglasses as a disguise, until she rose to accuse him of assaulting some of his patients.

“That’s not true, Faye,” he protested. “You know that.”

Flustered by the ambush, but trying to remain calm, Dr. Spiegel turned to Rivera and declared, “What I would like to know is why this woman— she’s playing judge and jury by herself, taking into her own hands and affecting the lives of innocent children—is permitted to just do this and get away with it.”

“You are lying!” Faye snapped at him angrily. “You raped your child, and you know you did!”

That shocking moment helped make Faye Yager a household name and led to retaliation. Dr. Spiegel sued for slander—successfully—but never collected the $5 million he was awarded.

“My mom simply filed bankruptcy,” says Josh Yager. “She didn’t have anything in her name.”

She did not even bother to respond to Dr. Spiegel’s lawsuit or to numerous others brought by distraught fathers. In case after case, unenforceable judgments were entered against Faye, who claimed to be indigent. “I’m a kept woman,” she used to quip.

“She was a force of nature,” says April Curtis, her voice cracking with emotion as she remembers those earliest days with the woman whose life would become inextricably entwined with her own over more than three ensuing decades.

Amanda, now grown, spent much of her life in the underground. She describes Faye Yager using one word: “Badass!”

❦ ❦ ❦

RAISED IN A RELIGOUS FAMILY, Billie Faye Wisen was a coal miner’s daughter from West Virginia, the second oldest of 11 children. Strong minded and independent even as a teenager, she was known to use a ladder to sneak out of the house at night with a younger sister, but the trouble they got into was harmless enough.

At 17, Faye married Roger Lee Jones.

The simple world she had known and understood came to a sudden end one morning in 1972, when she walked into her kitchen and discovered Jones molesting their infant daughter, Michelle, in her high chair. Faye threw a milk carton at her husband, then tossed all his belongings into the front yard.

He looked at her and said, “Faye, you really didn’t see that. We need to go to the doctor.”

In those days, just half a century ago, a woman couldn’t even obtain a credit card without her husband’s signature, and allegations of sex abuse in “good” families were rarely believed in court.

Jones, by all appearances a respectable accountant, claimed his wife had lost her mind and was dangerous—even to Michelle—and succeeded in having Faye committed to a mental hospital where she received at least 10 electroshock treatments.

Cobb County Superior Court Judge Luther Hames found Faye in contempt of court for absconding with Michelle after the initial custody hearing, and she spent 20 days in jail. He awarded full custody to her father—refusing to change his mind even when the child was diagnosed with gonorrhea at the age of four.

“I had no evidence of molestation.” Judge Hames protested to The Atlanta Constitution years later. “It was her word against his.”

By then, a lot of damage had been done to a lot of people.

Michelle later testified that Jones forced her to have sex throughout her childhood, until one day, at 13, she told him she wasn’t going to be his wife and would kill him if he touched her again. Apparently, he believed her and didn’t. But that didn’t stop him from molesting other children.

In August of 1986, police showed up at the mobile home where Jones was living with Michelle, by then 17, behind a used car lot he owned in Sarasota, Florida. A different young girl, this one 13, had told her parents she had been lured there by Jones, plied with wine, and molested.

They discovered a trove of videotapes showing Jones had secretly recorded himself performing sexual acts with girls as young as 10. Though he was arrested on multiple felony charges, he was released on bond and, predictably enough, fled. He remained at large for more than two years and became the first child molestation suspect ever placed on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted List.

The FBI characterized him as a “menace to society.” In 1990, a judge in Florida sentenced him to serve 40 years in prison. However, Jones is free today—a registered sex offender listed as living in Jacksonville.

In that time, Faye was transformed. Reunited with her oldest daughter for the first time in 15 years, the Sandy Springs interior designer declared war on what she called “court-ordered rape.”

Fueled with rage—and vindication—she set out not merely to stir public awareness and outrage over what she considered a broken judicial system, but to save children from their abusers using an underground network. “Yeah, I am breaking the law,” she bluntly told The Atlanta Constitution.

J. Tom Morgan had come to know and admire Faye Yager by the time he was elected district attorney of DeKalb County in 1992. “As a prosecutor, I could not endorse it,” says Morgan, a nationally recognized expert on the prosecution of crimes against children who is now teaching law in North Carolina. “But I certainly understood it, and I know that she helped some of the children in cases where we were not able to successfully prosecute the defendant. And I knew without a doubt that these kids had been abused.”

He turned a blind eye and never considered bringing charges against her in his jurisdiction. “I wouldn’t describe her as a zealot, like some people,” says Morgan. “She was driven by her own horrible, tragic experience with the system.”

❦ ❦ ❦

WITH REPORTS ON 60 MINUTES and in Life magazine, Faye was flooded with calls not only from women desperate for help, but also from volunteers offering sanctuary, and the Children of the Underground grew exponentially. “These were people who had no stake in it at all but were inspired to reach out to my mom, wanting to do something,” Josh Yager explains.

“The network was extremely loose,” he says, “but it operated as an underground railroad is supposed to, where they go to one person, that one person gives them to another, but doesn’t know where they go after that. And so, it becomes untraceable.”

Thus, Faye Yager did not know April Curtis and Amanda were living in the peaceful village of Hilton, New York, until April was arrested in 1993. A neighbor reported their whereabouts to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children—an organization Faye often condemned.

After she was returned to California, April scored a victory when she won custody of Amanda, but it came at a cost: The 11-year-old was forced to resume visitation with her father.

Two years later, in early 1997, the child became desperate. She says her father had threatened to put her in a mental hospital. She didn’t want to place her mother in legal jeopardy again. So, she called Faye herself.

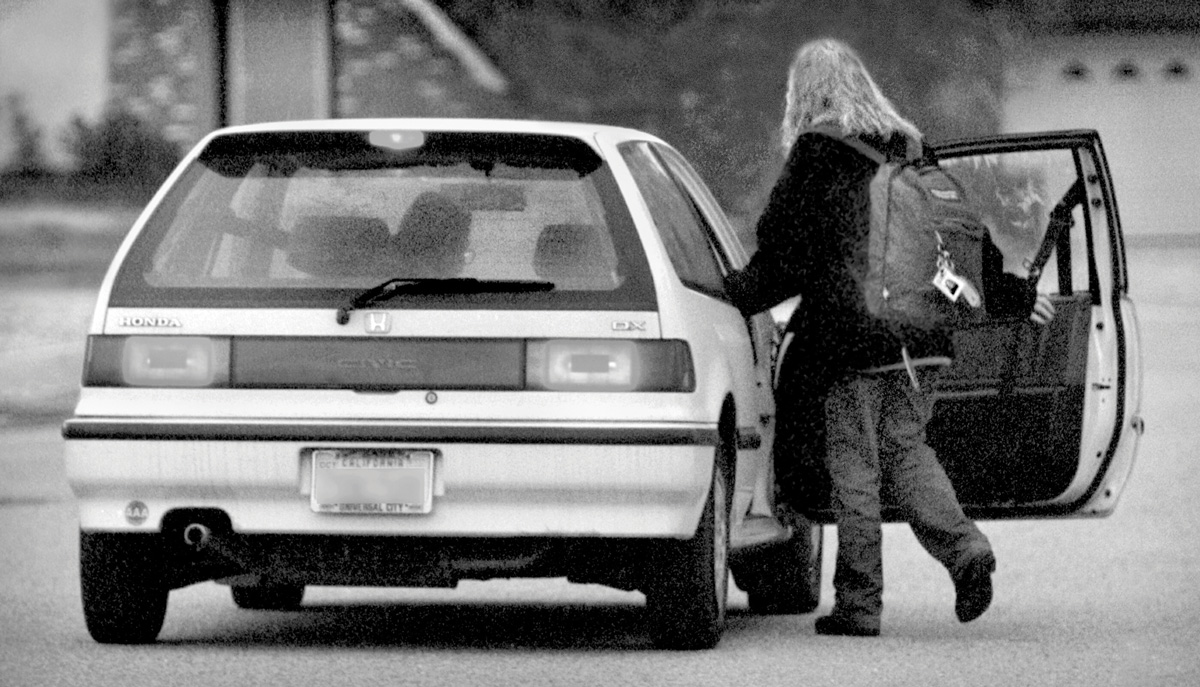

Photograph by Allan Detrich

Amanda, at 13, decided she would return to the underground, this time alone. She says Faye told her, “I’m going to take care of you, but also you’re going to take care of yourself, and you have to be ready to do that. You have to be strong. You have to commit to this.”

Determined, the girl did commit. One morning, her father dropped her at a school bus stop, and once he left, she walked up a side street and got into a car she’d been told would be waiting. “It wasn’t someone I knew,” Amanda recalls. “It wasn’t even someone I then stayed with. It was just someone who volunteered to do that.”

She stayed in the Mansion long enough to consider Atlanta her second home and even went to school here for a while. Her memories are of Six Flags and fireflies, along with humidity, heat, and thunderstorms. But she couldn’t stay.

Photograph by Allan Detrich

Amanda remained on the run—living for a while in France—until she turned 18. Then, she emerged from hiding and celebrated her freedom. She has not seen her father since the day she got into that car.

“This isn’t something that was fun to do,” she says. “It was a survival need. I didn’t go to high school. I never went to a prom or a sleepover as a teenager. Trying to relate to people, I always felt like I was a fraud.”

Unlike her mother, Amanda declined to participate in the 2022 documentary series Children of the Underground, produced for FX and now streaming on Hulu. “My father is still out there, and I don’t want him to know anything about me now,” she says.

She spoke for this article on the condition it would reveal no details about her current life—other than the fact she is still in counseling. “I can’t imagine getting to a point where I don’t need it,” she says.

❦ ❦ ❦

MOST OF THOSE WHO CAME TO FAYE YAGER and lived with her family were damaged or broken in some way, almost by definition.

“I remember a little girl asking me if I wanted to see her vagina,” Josh Yager says, lowering his voice. He immediately reported the incident to his mother, but such things have stayed with him over the years. “It would be false to say that I went through that period unscathed. I didn’t outwardly show it.”

Josh says he spent a good bit of time in the counselor’s office at school. “I ended up going to a psychologist for a year as well.”

Faye’s detractors were many—the most obvious of which, of course, were outraged fathers whose families disappeared. Most never saw their children again. Virtually all protested they were wrongfully accused, and at least some were.

Photograph by Allan Detrich

“If you look at all of the publicity, you really end up reading about, like, 15 cases,” says Josh. “It’s impossible to be correct 100 percent of the time, but I think what got covered in the news was often when there was a problem, and never the other thousand times.”

Mandie Ervin has never been the subject of a newspaper story or television report—even though, as a “missing child,” her face appeared on milk cartons distributed across the United States. She is amused by the inaccuracy of age-progressed photos on wanted posters distributed on behalf of the father who, for years, continued to hunt for her.

Six years old when she entered the underground, Mandie lived as Samantha Cristina Sandoval Anderson in Mexico until she was 18. Though she liked the country, she adds, “I did not grow up as a normal child and I missed out on a lot of things.”

Now 39, Mandie is a social worker. She is no longer in therapy but hopes to resume soon and has been in therapy for much of her life. “I feel like Faye helped us a lot and I’m grateful,” she says.

During the three months she and her mom lived at the Mansion, Mandie’s mother performed various odd jobs for Faye—including visits to cemeteries. “That’s how she was paying Faye back,” Mandie recalls. “My mom was helping her get names and create fake documents. Faye would use deceased people, based on when they had died.”

“You want to know what’s crazy?” Josh asks now. “She was in the middle of preparing for a trial.”

At the time, Faye was facing state criminal charges in Cobb County yet continued to operate Children of the Underground. “I mean, it’s nuts,” he says.

❦ ❦ ❦

MONDAY, APRIL 16, 1990, wasn’t a “normal” day—even for the Yagers.

For one thing, Josh saw himself on the front page of The Atlanta Constitution. In a large photograph, he and his older brother, Zach, are shown looking over their mother’s shoulder as she peruses an open notebook stuffed with documents. The picture accompanied a prominent feature article about Faye’s arrest on Saturday, two days earlier.

The nation’s best-known protector of children was accused of cruelty to children and other felony charges that could have sent her to prison for years and perhaps the rest of her life. But the underground wasn’t going to run itself, and Faye, released on bond, was out and about with Josh when a no-knock warrant was executed.

“I distinctly remember the raid at our house,” Josh Yager says. “It was the turning point for everything.”

FBI agents and officers from three metro Atlanta police departments swarmed the Mansion. Howard Yager, alone in the house, was terrified. He was sick in bed following a procedure for prostate cancer, though just how sick he did not yet realize. “I was in kidney failure,” Howard says. “They had to help me downstairs.”

Ordered to sit at the kitchen table, the doctor watched as his home and the belongings in it were trashed. “They ransacked the house, threw everything on the floor,” he says. “I sat in the kitchen watching them take stuff out.”

Photogarph by Calvin Cruce/Atlanta Journal-Constituion via AP

Faye and Josh arrived to find pandemonium. “Literally, the FBI just obliterated our house,” says Josh. “The search was overzealous to the point that it felt like a purposeful insult. I mean, every single room, every single drawer. How else can you interpret rifling through children’s underwear drawers and leaving all the clothing and toys strewn everywhere? It’s the scariest thing I’ve ever been through.”

Authorities seized about 40 files and VHS tapes, including one titled Lowering Your Cholesterol, but nothing Faye considered to be of consequence, nothing that would betray the location of any missing women and children or expose any of her confederates working for the underground.

“I’m not stupid,” she said. “I don’t keep anything that’s going to lead to any kids.”

J. Tom Morgan wasn’t surprised. “She was smart and methodical and a good planner,” he says.

Photogarph by Joe McTyre/Atlanta Journal-Constituion via AP

An engrossing trial in Cobb County focused in part on Faye’s assertions that she had discovered many of the cases brought to her involved Satanism, with fathers subjecting their children to ritualistic sexual abuse. Prosecutors argued she bullied children with suggestive questions, which unintentionally provided the answers she wanted to elicit, and played videotapes demonstrating several of her interrogations.

But her defense put the system on trial. Faye was a compelling witness, and so was her daughter Michelle, who provided straightforward, harrowing testimony about the ordeal she had endured most of her life—all because of obvious mistakes made years before in the very same courthouse.

After four weeks, as the jury deliberated, Faye, exhausted and fearful, slumped across the table, head down and arms spread. A short time later, her relief was evident as the verdicts were read in court: not guilty on all counts.

When it was over, jurors lined up to hug her.

She emerged as a heroic figure whose tragic past and good intentions made her all but immune to further prosecution. It was obvious no jury would convict Faye Yager. She was never charged again.

❦ ❦ ❦

ON A DRAB MORNING LAST SEPTEMBER, just as the earliest rain from Hurricane Helene reached Atlanta, Howard Yager’s longtime patients came to pick up their medical records, say a regretful goodbye, and express condolences. Yager wrote a few last prescriptions with a shaky hand.

“These people, I know all their family,” he says in a soft, gravelly voice. “Their mother, father, sister, brother—the whole family history.”

He came to Atlanta when he was drafted during the Vietnam War, but he was granted a deferment to work at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention while serving in the U.S. Public Health Service Commissioned Corps.

For 50 years, a small brick building in the heart of Buckhead has been home to his busy practice—easy to miss among the trendy shops and businesses on the narrow, increasingly fashionable Shadowlawn Avenue. The interior, however, was unlike any other doctor’s office in the city. As in an old curiosity shoppe, every bit of space, from the waiting area to three exam rooms, was adorned with antique medical items, a collection curated by his late wife.

In a back office, Zach Yager is in town from California, cleaning out old drawers and cabinets. “I keep finding her packets of Sweet’N Low,” Zach says sadly.

For the past several years, Howard managed to keep his office open a few days a week while tending to his wife’s health at home. Frail at 83, and grieving, he was persuaded by his children to give up his work.

It is not a happy retirement. He opened the practice in 1975, the same year he married the love of his life—for better or worse.

Scattered around the country and the world, children who grew up in the underground are now in their 30s and 40s. Some have surfaced here and there, but the whereabouts and life stories of the rest remains a mystery. Faye Yager always contended that the underground would continue without her, but many doubt that, and whether or not it still exists in some form is a mystery.

Most of the underground’s secrets, it would seem, died with Faye. But not all. Subpoenaed in a civil case at the age of 12, Josh Yager repeatedly invoked his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination.

Much of the information so eagerly sought by police and the FBI was known to a little boy who was along on visits to safe houses across the United States and even abroad.

“They thought they were going to get the answer there,” he says of the futile search at the Mansion. “And I knew all the answers, actually. I went with her to all those places. I met the Sallys.”

Soon after his mother’s death, while grieving, Josh emptied a very full storage locker his mother had kept for many years.

He declined to say what he found inside it.

This article appears in our February 2025 issue.

Advertisement