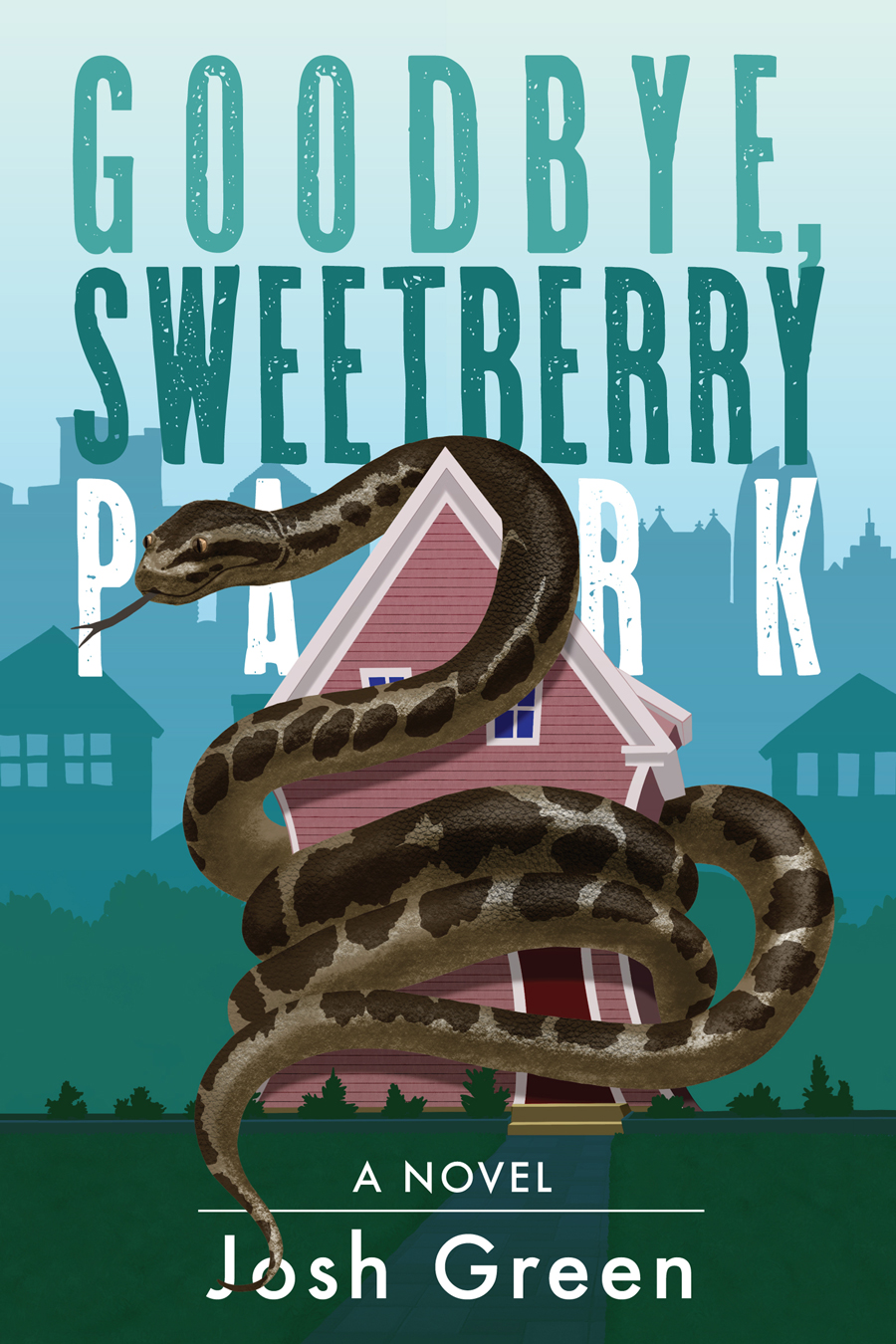

Courtesy of the Sager Group

What happens when you mix together Atlanta gentrification, escaped venomous snakes, and a drunk narrator nicknamed God? Anarchy that borders on being a little too real.

Goodbye, Sweetberry Park (Sager Group) is the second novel from award-winning journalist Josh Green. By day, he edits development publication Urbanize Atlanta and also writes for several publications, including Atlanta magazine. By night, his news-reporting career bleeds into his fiction. His first, Secrets of Ash, follows two brothers struggling with PTSD in north Georgia, for which Green earned a nomination for Georgia Author of the Year.

This book follows an experienced and jaded journalist, Archie “God” Johnson, of Nigerian and Scots-Irish descent, who inherited from his racist White grandfather an old Victorian house in the ‘80s in the dilapidated neighborhood of Sweetberry Park. After 30 years of struggle, his neighborhood is under threat from developers. They hope to turn a small shotgun house street, with a history of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. living there, into a developed “preservation” project called Sweetberry Lanes. God and other Sweetberry Park residents try every measure to save their neighborhood from development, which results in several satirical twists and turns that devolve into chaos.

Photograph by Lola Green

We caught up with Green to discuss Goodbye, Sweetberry Park and how his career in journalism played into this novel. Aptly, our discussion on the patio of a Decatur coffee shop had the background music of construction.

You dedicate the book to Miss Anna, who was the focal point of your 2016 story with Atlanta magazine, “The Gentrifier,” which takes place in Kirkwood. After reading Goodbye, Sweetberry Park, I see several parallels to that essay, from the relationships in the book to an Atlanta neighborhood changing rapidly. Was there something that you still wanted to live out through a book of fiction?

One million percent yes. I had done months and months of research for that Atlanta magazine story, including in the bowels of Emory University and Atlanta History Center, and came across a lot of stuff that was troubling and fascinating about gentrification in the area I moved to and still live in Kirkwood. But I couldn’t fit everything into that magazine story, from the little anecdotes of what people said had happened with White flight and changes of demographics back and forth through the neighborhood. Goodbye, Sweetberry Park ultimately is a work of fiction, but these scenarios were so moving and inspiring for the book.

With Miss Anna, I wanted to give her that nod, and not just her, but several people in Kirkwood over the years. I pay homage to her through the Genteel character, a former blues star who has been in Sweetberry Park forever but is presented with a real estate offer that’s hard to pass up. She has this gigantic personality, and I tried to capture bits and pieces from real people and put them together into this pastiche of the matriarch of the neighborhood who’s tragically fading out, like what we see with many legacy residents in these areas. So my neighbors were inspirations, as were some of the well-known people in the real estate world of Atlanta.

This is your second book, after Secrets of Ash, which follows two brothers struggling with PTSD in North Georgia. Goodbye, Sweetberry Park is a huge tone shift into satire with an unreliable but well-meaning narrator in “God.” What were some of the things you wanted to try in this style of writing?

I’ve been putting this book together for seven years, working on it off and on. I ended up totally shelving it during the early pandemic because it just wasn’t the right time. Who’s going to want to read a book poking fun at gentrification when they’re on lockdown, you know? One of the frustrating things with the creative process is that sometimes it’s just not the right time in society to do something.

After the pandemic, I feel like it’s more than ever the right time because of the American dream and how it’s more impossible for a lot of people. My heart breaks for younger people trying to break into Atlanta the way I did 12 years ago. There’s also Beltline mania, which has been here but it’s ramping up with development and now the finishing point of the trail is on the horizon. And as people have famously flocked away from New York and L.A., Atlanta is still growing. It’s become a magnet for new people, but that inevitably creates friction. My thought is that people are ready for a fresh perspective on these issues right now. I wanted to approach it in a way that hadn’t been done before, with a character who is unique, weird, and wacky, but also lovable, wanting to save his neighborhood. God’s a jaded older journalist who has seen it, done it, and failed a million times. To me, that’s really American.

How did your own experience as a journalist, especially focusing on development, shape some of the book’s events, which often satirize the spectacles of media?

I think with all the books I put together so far, I want to use my imagination and creativity to say something about what’s really going on right now around us. Basically, 90 percent of the book is infused with stuff I’ve seen out about the world or written about or people I’ve talked to. My journalism career couldn’t be more inextricably linked.

My day job used to be covering crime in Gwinnett County, so all day long, I’m running around trying to get the exact terrible scenario that happened right, and when I’d come home at night, I’d just try to purge it from my system by writing fiction and make art out of it. The same thing happened this time but in a less macabre way. I’m always reporting on the physical evolution of this wild and amazing city. You see stuff that pisses you off, or even things that make you laugh, and grab those little nuggets and try to transmute them into this imaginary world that hopefully says something about today in town.

In the book you nickname Atlanta, CenterTown, trademarked and everything by the fictional developers. What’s behind those choices?

The North Star for the book was the word ridiculous, which I think is fitting for what’s going on in real life too. I also want to just kind of take a jab at all of this to call it CenterTown with the capitalization and trademark symbol. It’s a succinct way of saying look how corporate and infused with sameness everything is. It’s so disconcerting to look at photos of other cities and think you’re looking at Atlanta’s new development, because the same people are doing it. It’s the same copy-and-paste blueprint over and over. It has happened with Austin. It has happened with Dallas. You see it everywhere like it’s commercialized.

We also get the gentrification lexicon from the narrator, with mention of real things such as legacy owners, DINKs (“double income no kids”), pop tops, but also some made-up terms such as “dickfaces” and “duds.” Talk to me about the vocabulary you use in the book.

I included the lexicon to speak to the source of judgments, naming things, sometimes with succinct little acronyms that essentially divide people. Honestly, a huge inspiration for that was Facebook comments and Nextdoor. And some of it isn’t all bad. The phrase “legacy” resonates, and it’s an homage to people who live in gentrified neighborhoods and stick it out. But I did make up a few things and threw it in there for spice.

Throughout your ironic twists of gentrification, we also see a difference between protection and preservation with the fictional development project Sweetberry Lanes. What inspired you to start this discussion in the novel?

Change is inevitable in any city, especially a healthy city, but you also see a lot of big talk over the years from developers that absolutely doesn’t come true, especially when it comes to preservation. I could drive you around and point to so many townhome developments, very bland buildings, that were something much more unique and interesting before. And they started out as a preservation project, which became a bold-faced lie.

I also think there should be more discussion around gentrification. For younger people around here, it could mean good change, but for people who have been here forever, or people who are not White, it could mean another. I’ve also heard from so many capital-motivated people who speak of gentrification like it’s a synonym for improvement, and there’s nothing else to think about it. They’re not being evil about it; it’s just the way their mind is set toward the issue.

I can see that tie into the snakes, who invade the neighborhood of Sweetberry Park in the novel. What do they mean to you?

The snakes were this idea of this venomous, unseen thing that’s motivating people’s behavior in so many ways. That could be racism, ageism, or classism, which all motivate people, even if you don’t see it. And it makes them do weird, bad things. Also, the snakes are straight-up real incidents in Atlanta that have happened here like in Piedmont Park, or there was an escaped boa constrictor that burrowed under a trail where I walk my dog all the time. It’s a very human and natural thing to be on edge, but nothing got a hold of Rocco. So what’s the real danger?

If you want to shout out a few coffee shops, where in Atlanta did you work on the book?

Maybe it’s strange, but I felt I wanted to be close to where this fictional neighborhood was, which is a mashup of neighborhoods. So I would go to the coffee shops in the thick of it, such as Taproom in Kirkwood, Oakview Coffee in downtown Oakhurst, Inman Perc, Dancing Goats in Grant Park, and Little Tart off Memorial.

Advertisement